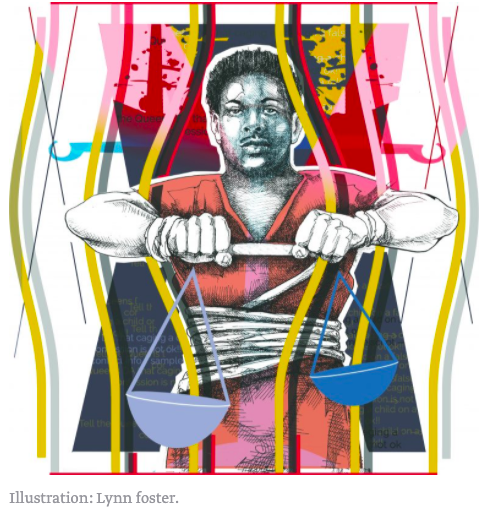

The Gamble of His Life

Prakash Churaman's first murder conviction was overturned. Now, he's risking everything on a second trial before the same Queens prosecutor-turned-judge who railroaded him before.

“Hi, my name is Prakash Churaman. I am currently incarcerated on Rikers Island. I was arrested in December 2014 for a crime I did not commit and I’m still to this day, awaiting a fair trial. It’s been almost six years now. I was arrested at age 15. I’m now 21 years old. I go to Queens Supreme Court and basically, I’ve been voiceless and silenced since the day my freedom was taken from me. Ever since my freedom was taken from me, over the last six years, I’ve been experiencing nothing but injustice and inequality. I need your help, please.”

That was the message we received on the hotline of our WBAI-FM radio show, Working Class Heroes. And that’s how we discovered the case of a 21-year-old Guyanese immigrant who has been locked up in Rikers Island since he was 15 on a murder charge — even though his conviction has been overturned.

“Since his arrest on December 9, 2014, Prakash has been waiting for a fair trial while incarcerated,” says his lawyer, Jose Nieves. “His years of incarceration have in fact rendered his right to a presumption of innocence meaningless and the right to a fair trial merely a mirage.”

Churaman’s case exposes many of the problems with the Queens criminal-justice system — including not only the failure to provide speedy trials, but also coerced confessions and impunity for judicial misconduct — that were brought to public attention in 2019 by public defender Tiffany Caban in her nearly successful underdog campaign to become the borough’s new district attorney.

But as that initial message on our voice mail indicates, Prakash Churaman’s story is also about how a young man has endured the trauma of youth incarceration and built a defense team for himself inside and outside the courts to win a conviction reversal and bail release from a Queens machine that has resisted every move toward justice.

Last year, Churaman was offered a plea deal that would have allowed him to get out of jail soon, but he refused to admit guilt for a crime he says he never committed. He is risking many more years of life in a cage with a new trial that will be presided over by the same judge whose misconduct in the original case led to a wrongful conviction.

He knows that he’s taking a tremendous risk, but he feels he has no choice. “That’s me accepting guilt for a crime I did not commit,” he says. “I can’t do that. I can’t be a victim to the system, another statistic for the system. All they care about is the conviction rate. They don’t care about whether a person is innocent or not.”

A Brutal Murder, A Questionable Confession

In 2014, three men staged a home invasion in Jamaica, Queens. During the robbery, 21-year-old Taquane Clark was shot to death, and his uncle, Jonathan Legister, was wounded. One of the assailants was also shot, leaving behind DNA evidence that was traced to 28-year-old Elijah Gough, who was found guilty in 2018 and sentenced to 65 years to life.

Also in the home that night was Olive Legister, Jonathan Legister’s mother, who was held hostage during the robbery. After the incident, she told police that she believed that the voice of one of the assailants belonged to Prakash Churaman, a friend of Taquane Clark.

Taquane and Prakash met playing basketball in the neighborhood, not long after Prakash had moved away from his father in Florida to stay with his mother in New York. “I introduced myself and we got to know each other and our bond just grew naturally,” Churaman says. “[My father] was constantly abusing me and beating on me, so when I turned 11 or 12, maybe, I called Children’s Services down in Florida and I told them, ‘Listen, I don’t want to live with my father anymore. I want my mother to have custody of me.’”

Prakash also found his way into trouble and the Queens criminal-justice system. “I’m not an angel,” he says. “Sometimes I would cut school, hang out with friends, you know, normal teenager stuff.”

In early 2014, police responded to a call from Prakash’s mother that he was running away from home and found what he says was a little knife in his

apartment. He was arrested and sent to a Bronx juvenile facility for seven months. He was released on good behavior that November, not long before the home invasion and murder of his friend Taquane Clark.

Acting on Olive Legister’s tip, police arrived at Prakash’s door early on the morning of December 5, 2014. “They came to my apartment without any warrant and they put me in cuffs,” Prakash says. “They had me in a minivan for about three hours — mind you, from where I live to the 113th Precinct, it’s only about 10 minutes.”

When he finally reached the police station, the 15-year- old was put in a small room, where he says he was handcuffed to a pipe on the wall and interrogated by Detectives Daniel Gallagher and Barry Brown.

“Barry Brown was the one that was doing all the cursing and yelling at me,” Churaman recalls. “He did most of the manipulation. The other one, Gallagher, was mostly quiet, acting like he was my friend, and he really wasn’t. They both tag-teamed, played good cop/bad cop.”

“I really did not know what to do,” Churaman continues. “I was lost. I didn’t know what they were talking about. I don’t even know why I’m here. Eventually, I broke down. At one point in the interrogation tape, I said, ‘I’ll say whatever you want to hear.’”

“Mind you, at the time I was taking psych medication. I was taking Wellbutrin because I suffer from depression and anxiety, so they definitely took advantage of me. They didn’t allow me to take my medication or anything.”

Churaman’s mother was present during the interrogation, but she now says she wasn’t aware of the consequences, given the language barrier. She emigrated from Guyana with Prakash and his father when Prakash was a little boy. Worried that her boss might lay her off if she didn’t get out of the precinct and get to work, and perhaps not understanding the stakes of the situation, she urged her son to cooperate with the police.

“My mother was present, but she’s illiterate,” Churaman says. “She doesn’t have no educational background, nothing. She folded just as well as I did, basically.”

With no physical evidence connecting him to the crime scene, Prakash’s confession would be a crucial element in his conviction for “felony murder” (a uniquely American statute directed at those who commit a serious crime while a homicide takes place) in December 2018.

His conviction came one month after Detective Brown made the news during the highly publicized trial for the murder of jogger Karina Vetrano, which resulted in a hung jury over concerns that Brown had improperly coerced a confession out of the defendant, Chanel Lewis. But Prakash Churaman’s jury never got the opportunity to learn about Brown’s tactics, thanks to the actions of Judge Kenneth Holder.

Trapped Inside the Queens Machine

In his 2018 trial, Churaman was represented by the noted civil-rights lawyers Ron Kuby and Rhiya Trivedi. But Judge Holder refused to allow them to present an expert witness on the subject of juvenile forced confessions — despite the fact that Churaman’s confession was the prosecution’s primary evidence in a case with no physical proof linking him to the scene of the crime. Denied this crucial information, the jury found Churaman guilty and Holder sentenced him to nine years to life.

“When I went in front of [Holder] to get sentenced,” Prakash says, “he told me that had I been 16 years and older, he woulda made sure I’d never see daylight again.”

Like many Queens judges, Kenneth Holder is a former prosecutor who worked in the Queens District Attorney’s office from 1985 to 2005. For most of those two decades, the office was headed by Richard Brown, infamous in criminal-justice circles for pushing “tough on crime” policies long after crime rates plummeted across the city.

“Historically, the Queens DA’s office has shown deference to the NYPD,” wrote journalist Ross Barkan in 2019, “failing to aggressively pursue police brutality cases. Queens prosecutors are unusually punitive, employing tactics unseen in other city offices … . Assistant district attorneys will join police to interview defendants before they are even arraigned, hoping to secure incriminating statements that will lead to quick convictions.”

Kuby says felony murder statutes lend themselves to improper police interrogations “because what the cops invariably do in felony murder cases is tell the defendant, ‘We know you didn’t kill anybody, we know that you didn’t intend for anybody to get hurt, we know you’re not a murderer, but just admit that you were there for the robbery.’ And even innocent people, under those circumstances, will say, ‘Yeah, I was there, I was down with the robbery,’ not knowing that they just confessed to felony murder.”

“Some lawyers said the [Queens DA] office’s pretrial plea policy was coercive and manipulative,” New York Times journalist Eli Rosenberg wrote in 2015. “They said that the script used to interrogate suspects before their arraignments, wording that was declared unconstitutional in 2014, was still troublesome, despite revisions.”

Issues such as these led to the groundswell of support for Tiffany Caban’s 2019 campaign to succeed Brown after he died in office that year. She came within a few votes of pulling off a remarkable upset over Melinda Katz, the preferred candidate of the Queens Democratic Party bosses, who have long handpicked candidates for elected judicial and prosecutorial positions.

But while Caban’s campaign and those of other progressive aspiring DAs nationwide have drawn attention to the issue of prosecutorial abuses, the issue of judges’ misconduct and impunity deserves just as much scrutiny.

The system is premised on the idea that judges like Kenneth Holder will be unbiased, even though many of them have come almost directly from the same offices as the prosecutors now arguing before them. And when they seem to fall short of that ideal — since 2008, Holder has had 27 cases overturned, almost all of them for pro-prosecution abuses such as excessive sentencing and improper jury instruction — there seem to be no consequences.

Eighteen months after Churaman’s conviction, Kuby and Trivedi won a reversal in a state appellate court, on the grounds that the jury should have been allowed to hear testimony about false confessions. But the overturning of his conviction has had surprisingly little impact on his life. Because judges aren’t removed from cases in which their decisions have been reversed, his new trial will be presided over by Kenneth Holder.

Until this January, when his new lawyer, Jose Nieves, finally won his release on bail, Prakash remained in Rikers Island, because Judge Holder continued to deny him the chance to prepare for his second trial from the home he was taken away from when he was 15.

Fighting from the Inside

Life inside Rikers has taken an enormous toll. Churaman has attempted suicide twice, and at one point was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. A victim of anxiety and depression even before his arrest, he now believes that he is also suffering from PTSD.

Despite his struggles, Churaman became friends with other incarcerated youth on Rikers Island and met people who continue to provide him with support and friendship. One of his most important early allies was Jacob Cohen, who ran a music program in Rikers Island for adolescents and young adults.

“Everyone has horrible situations in there,” says Cohen, “but Prakash’s was a particularly sad case, because he said he was innocent and locked up for a crime that occurred when he was 15 years old. And he had basically no support.”

“Eventually, he asked me to help him organize a Kickstarter to help him raise funds so he could hire a lawyer,” says Cohen. “I made a one-minute video for Instagram that included drawings of him that I did, and we recorded a phone call that was basically him saying ‘I’m accused of a crime I didn’t commit, I’m poor, I need funds because I don’t have a lawyer, I don’t have legal representation.’”

Jacob’s advocacy for Churaman eventually cost him his job, but it brought the case to the attention of Kuby and Trivedi. Churaman was eventually able to pull a small support team together, including members of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, which started to build publicity around his case.

Day after day, Churaman left the same kind of messages we received at Working Class Heroes for anyone he thought might help. By December 2020, those efforts started to pay off as his support team organized a rally in the snow outside the Queens courthouse.

A new wave of publicity in the aftermath of that rally resulted in a campaign to call on Queens DA Melinda Katz to drop the charges. Jose Nieves got bail granted, and his expanded support team raised the money. On January 19, Churaman, now 21, was able to come home under conditions of house arrest.

The Fight is Far From Over

When Prakash Churaman turned down a plea deal that would have drastically reduced his remaining prison sentence, he was taking a massive gamble that it is possible for a poor immigrant of color to win a measure of justice from the Queens criminal-justice system. His lawyers at the time, Kuby and Trivedi, advised him against it.

At the same time, the District Attorney’s office’s willingness to offer such a seemingly lenient deal for the serious crime of felony murder indicates that it might not have been very confident about its case. Churaman is confident that justice will prevail, and that has inspired supporters to rally to his cause.

“[I’m] someone who grew up in Queens and walked out of this courthouse many days as a young person,” said Cory Greene of How Our Lives Link Altogether (HOLLA) at the December 9 rally outside the Queens courthouse. “So when I got that call from a young person who had been in prison since they were 15 and that person still had the audacity to fight to want to be free, that spoke to my spirit personally. It didn’t matter if it was raining, sleeting, or snowing, if I had an inch or energy to be here today to speak to the courtrooms, to speak to you all out there—but really to speak to my little self that was 15, that was 16, that was 17 in there, and I didn’t have the heart that Prakash had. I didn’t know how to fight like he knew how to fight.”

But with his case still in the hands of a judge who suffered no consequences for his improper conduct in the first trial, Churaman still faces long odds.

“Prakash faces a second trial,” Nieves says, “in a broken criminal-justice system that is dysfunctional because of institutional racism, coercive police interrogation tactics, prosecutors that are more focused on getting a conviction rather than doing justice, and a global pandemic that has brought our system of justice to a grinding halt forcing criminal-justice-involved citizens to wait in a perpetual purgatory until they can have their rights as citizens acknowledged.”

When Melinda Katz narrowly defeated Tiffany Caban to become the new Queens district attorney, she responded to the cries for reform by creating a conviction integrity unit to investigate wrongful convictions. But Prakash Churaman has already had his conviction overturned, and he still spent much of his adolescence in jail. He would get his case reviewed by the conviction integrity unit only if he’s convicted a second time.

Katz’s office said its policy is not to comment on ongoing cases.

As the February 10 date for his retrial approaches, Prakash is home with his mother and grandmother, but his transition to civilian life, as brief as it may have been, remains a struggle.

“They robbed me of everything, man, everyone who was in my life,” he says. “All that mental anguish and trauma, it took a toll on me, especially in regards to my mental health. I was kidnapped for six years. The wrong that’s been done to me is irreparable. No matter how much compensation I receive for getting wrongly convicted, I’ll never get back the time I spent behind those barbed wires.”

“I’m going to prove my innocence and continue freedom fighting and fight for those who are in my situation,” he continues. “There are lots of juveniles in the system, just like me. The system is really cruel and nothing’s going to happen and if we sit around and let them continue their cruel and unusual punishment.”

Published at The Indypendent, Feb 9, 2021